The Musings of Two Hellbound Hearts

Mike – Hey Danny. Thanks for joining me on this first Appendix i, which is a look into the inspiration behind our creative works. We could have started anywhere, but we start with Clive Barker and Hellraiser. I mean it’s Halloween season right?

So I know that Hellraiser was one of our favorite movies back in the day. And being honest, it is one that I always pop on during Fall at least once per year. Having something that has been a part of your life for so long, it has to creep into your creativity right? Or at least be good enough to keep coming back to. So, what do you find so attractive in the Hellraiser series (this includes movies, comics, and books)?

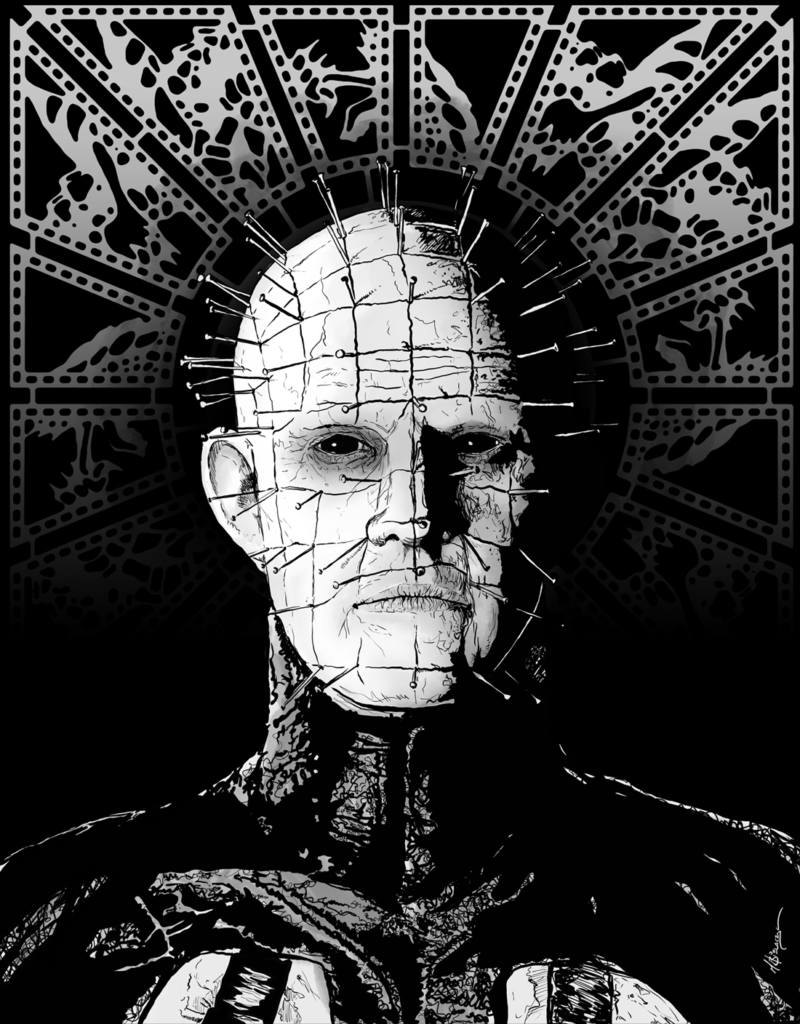

Danny – I love the cenobites in The Hellhound Heart and the movie adaptation. I remember the first time I saw Hellraiser: the ads emphasized Pinhead as the antagonist, but in fact, the cenobites play a fairly small role, and the real antagonist is the resurrected uncle Frank, who has escaped the cenobites.

And when the cenobites do finally appear, it’s unsettling and exciting in a way I’ve never quite been able to put into words. There’s nothing quite like it in horror. Each cenobite has been altered in some way to cause intense suffering—but they revel in suffering. They’re not mindless demons killing and maiming for no reason. They’re intelligent and powerful. They have poise and seem in perfect control. They take only the people who solve the puzzle box—which usually means people seeking the furthest extremes of pleasure. And that’s where their dark philosophy comes in, regarding the overlap of extreme pain and pleasure. The people who solve the box come to regret the choice.

Mike – The best villains spend the least amount of time in the spotlight right? When the cenobites first show up, Pinhead utters that iconic line – “demons to some, angels to others.” That line changed how I viewed bad guys. This was no slasher who just popped up and killed people. He was not just a tagline. This was something new. It’s something both of us always use in our creative works. No single duality, good vs evil, these cenobites were smart and dangerous, but they were summoned. They were wanted. And they were a reflection back on the worst desires of people. And yes some regret the choice of opening the box… but others do not regret it and they become cenobites. The real monsters are humans and their desires.

Danny – I’m glad you mentioned that quote. The full quote is “Explorers in the further regions of experience. Demons to some. Angels to others.” And that’s the key to understanding the cenobites: explorers of experience. They’re sensual beings—obsessed to the point that their quest for new sensations overtakes everything else…and they’re so good at navigating those outer reaches of sensation that they’ve become like sherpas for people who have sought their guidance. It almost sounds tempting, even as I write the words, but of course, an eternity of extreme, relentless sensation is exactly what we might expect from hell.

So you’re right. I remember asking the question, “Are they evil?” I leaned toward yes, but when I really thought about it…were they? That ambiguity was part of what made them terrifying. I realized that a lot of the most terrifying things in life can also be tempting. Like characters in a haunted house who know the danger, but their curiosity drives them forward against their better judgment.

That quote also illustrates another aspect I like about Pinhead, in particular. He’s the master of short, eloquent, quotable bits of dialogue. I’d almost call some of them one-liners, except the early ones never felt silly. He would convey a lot of information and a sense of dread with only a few words.

Here are some other examples I always loved:

“Oh, Kirsty. So eager to play, so reluctant to admit it.” This communicates so much. The implication that it’s Kirsty’s own desires that brought her here, and she just needs a little time to accept it. The word “play” used in place of what most might call “torture.”

“But please, feel free, explore. We have eternity to know your flesh.” Not only does this make you understand that these are eternal beings with all the time in the world, but you can feel it. He doesn’t mind if she evades her damnation a little longer because her fate is inevitable.

In response to a security guard threatening him with pain: “What you think of as pain is only a shadow. Pain has a face. Allow me to show it to you.” This one’s just a cool line. I actually sampled this line for a song I recorded in the late 90s.

continued below image…

Mike – So how does Hellraiser, or Clive Barker in general, influence your work these days? In our projects with the Dark Return or your own personal projects?

Danny – Clive Barker is arguably the reason I write. I’d toyed with writing since I was a kid, but it was reading Clive Barker’s books in high school that really cemented the goal. So maybe I wouldn’t be doing this at all if not for his work.

As for how he influenced my writing, he influenced me to take a well-tread genre and do something genuinely different with it. There are far stranger takes on genre than what Barker did, but he was my introduction to it. But the influence of Hellraiser is mostly in tone. I grew up obsessed with horror, and I thought it was all slashers, monsters, and the occasional psychological terror. But the cenobites, while scaring me, made me want to get closer to them rather than away from them. I wanted to learn more. And he didn’t do that by pulling back…the cenobites are about as dark and brutal as horror gets. But they were interesting and made me think and reflect. That has stuck with me.

How have cenobites influenced you and the development of the Dark Return?

Mike – I think I can see the DNA of Clive Barker antagonists throughout my work. Both of us have also used subtlety and nuance in our struggles between two opposing forces. So much that I can’t even say good vs. evil. The cenobites are evil, as they do violence upon others. The line is blurred since they tend to go after those who seek them. Though in the movies they pursue Kirsty, stating basically that “she wants it, but won’t admit it.” Which may be the easiest example of exactly how vile they are. This may have answered one of my oldest questions, what makes an antagonist wrong? It is when they cause unwanted pain and violence on another.

Another part that caught my imagination was Leviathan. While the cenobites were connected to the world, Leviathan was an otherworldly horror. The image of a giant evil rhombus floating over a never ending maze was maybe the first cosmic-like horror that etched itself into my mind. And that maze also stuck, in my own writing I see the extra dimensional plane that Kaldrath was imprisoned in looking much like this labyrinth.

A lesson that many creators can take away from the Hellraiser movies is, don’t lose your mystery! The more the cenobites became cliche and explained, the less scary they were. I mean a bad guy should never shoot CD’s from his throat. Just saying.

But seriously, I would say the biggest thing these stories left me with was the idea that there were more than two sides to a coin. It’s not a struggle of good vs. evil, there is too much in this world, let alone universe, to be simplified into such a tiny binary argument.

Danny – I understood the situation with Kirsty a little differently. There’s another quote from Pinhead where he says, “It is not hands that summon us. It is desire.”

I think what the story is exploring is our own struggles with inner demons. On the outside, Kirsty doesn’t seem like the sort of person who would seek the cenobites, and yet, that’s exactly what she did. Their presence is a manifestation of her desire. She was just clever enough to figure out a way to escape her fate while also making Frank go away.

Regardless of that, if she says no, and the cenobites take her anyway—even if they can see desire in the dark recesses of her heart—that certainly makes them villains. I don’t think their status as the evilest characters in the story is in dispute here (even if we find ourselves hating Frank much worse)…but they’re interesting villains because of all the factors we’ve discussed.

Mike – Maybe the most villainous thing is that they enable or expose humans to be their worst. The most horrible acts of violence in the movies (at least the first 2), are all committed by the humans. Which was a brilliant twist on the horror movie, most of which came out during that time were simple slashers. Hellraiser gave more. It had cosmic mystery, compelling monsters, and a commentary on what humans were capable of. It was truly horror from all sides.

Danny – Exactly. Pinhead was the draw, but the horror was the humanity. The cenobites seem to be a reflection of us. They’re manifestations of what’s buried deepest inside us. It certainly wasn’t the first horror to explore that idea, but it did it well, and it was timed perfectly, as you said, when theaters and video stores were filled with A Nightmare on Elm Street, Friday the 13th sequels, and a whole lot of killer monsters. This one stood out.

Part of what made it work was the balance it struck between entertainment and the exploration of its themes. It wasn’t a typical horror movie, but it also wasn’t a challenging piece of art-horror like Don’t Look Now.

It was a bridge that took me from slashers to what later became my favorite horror, like David Cronenberg’s movies, which led me even further outward into stranger stories.

And it’s worth pointing out that Clive Barker had no experience in making movies and even tried to check out a book on making movies at the library, but it was already checked out. And still, somehow, he made one of our most timeless horror movies.

Like this Article? Learn more about this Issue.